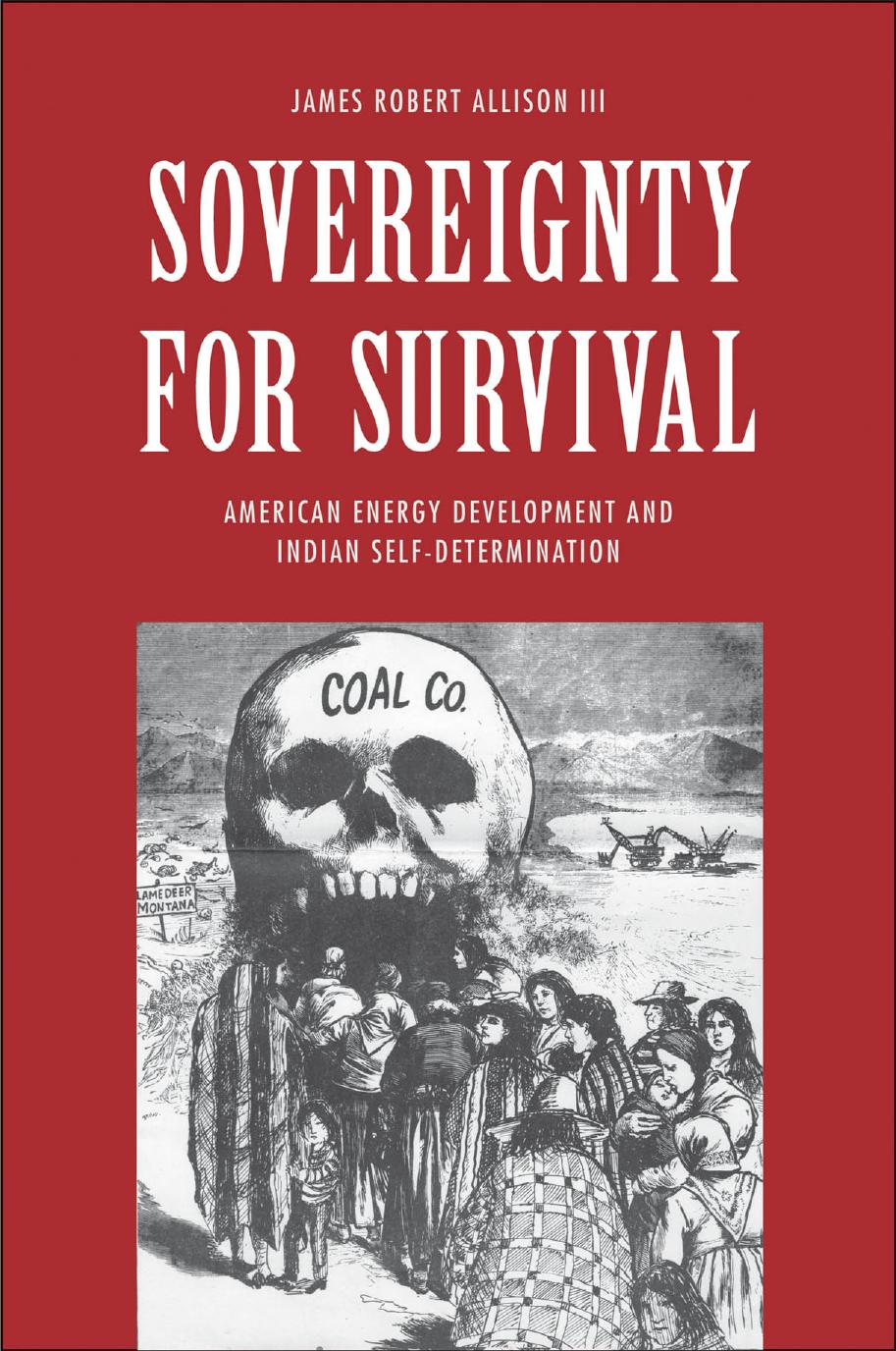

Sovereignty for Survival by James Robert Allison

Author:James Robert Allison [Allison, James Robert, III]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2015-08-14T16:00:00+00:00

7

Recognizing Tribal Sovereignty

AS THE ENERGY tribes gathered for the September 1980 annual meeting of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes, they had good reason to be optimistic. Earlier that year, the federal government had made good on its $24 million pledge to support Indian energy development. The tribes had put these funds to work developing an extensive Indian resource inventory, conducting feasibility studies for new energy technologies, breaking ground on tribal mining projects, and continuing to educate tribal leaders on resource management techniques. In addition to the flow of federal dollars, the Department of the Interior had also just proposed new regulations for mining on Indian lands that promised to minimize “any adverse environmental or cultural impact on Indians, resulting from such development” as well as guaranteeing the tribes “at least, fair market value for their ownership rights.” The key to delivering these results was a new provision authorizing Indian mineral owners to enter into flexible mineral agreements that “reserve to them the responsibility for overseeing the development of their reserves.” These “alternative contracts” to the standard lease form would finally provide tribes with the control necessary to ensure mining did not threaten their indigenous communities.1

Reflecting the improved relationship with the federal government, CERT held its 1980 annual gathering in Washington, D.C. There, Chairman Peter MacDonald explained that the meeting’s purpose was to further explore “how to go about building a truly meaningful energy partnership between the tribes and the federal government.” Federal officials played their part enthusiastically: Energy Secretary Charles Duncan delivered the keynote address, and numerous governors, senators, and members of Congress attended the event to endorse the strengthening tribal-federal relationship. The three presidential candidates—Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and the independent congressman John Anderson—either personally attended or sent congressional delegates to voice their support for tribal autonomy and lobby for CERT’s endorsement. Speaking at the concluding press conference, Senator John Melcher of Montana captured the shared sentiment: “No longer can the federal government dictate the terms of energy development on Indian lands [and] no longer can the government decide what is good for the Indian people.” All the years of work seemed to be paying off. Again, optimism abounded.2

But to those paying close attention, there were rumblings of trouble in the recesses of the conference’s meeting hall. In fact, despite the recent contribution of funds, promising new regulations, and supportive messages, Wilfred Scott, CERT’s vice chairman, noted “mixed signals” coming from federal officials over whether tribes had the legal authority to manage their own minerals. The specific source of these concerns was a recent oil and gas deal struck between the Northern Cheyenne and the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) that deviated from standard lease form and procedure. This agreement, like a lease, conveyed exploration and production rights to the oil company, but it retained for the Northern Cheyenne certain ownership interests in the project. Moreover, the Northern Cheyenne procured this alternative oil and gas contract through private negotiations rather than via the standard public notice and bidding process.

Download

Sovereignty for Survival by James Robert Allison.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1707)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1622)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1553)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1455)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1426)

Tip Top by Bill James(1414)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1374)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1359)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1352)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1336)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1315)

F*cking History by The Captain(1302)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1300)

American Dreams by Unknown(1285)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1272)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1257)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1211)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1173)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1125)